Generation V: Nathaniel Joins the Great Migration

Nathaniel Colborn (also Colborne, Coalborne, later Colburn) was born in Woolverstone, Suffolk, sometime within the year preceding 12 September 1611. The priest who baptized him, with whom he eventually emigrated to America, was a Cambridge-educated Puritan “nonconformist” named Timothy Dalton.

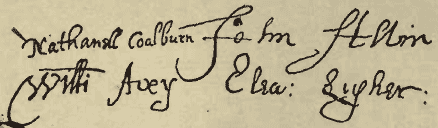

Illustration of a Puritan minister being pulled from his pulpit by religious opponents (late 1500's) Ref

The early 1600’s saw a growing conflict within the Church of England. Influenced by the thoughts of Swiss theologian John Calvin, many objected to church practices that seemed too close to Roman Catholic ritual, advocating a more "pure" form of worship. They believed in strict observance of the sabbath, and wanted churches to be governed locally by groups of elders (presbyterianism) instead of through a hierarchy of bishops and archbishops (episcopalianism.)

Attempting to suppress this "Puritan" challenge to their authority, the bishopric adopted increasingly authoritarian measures, including the persecution and execution of nonconformist priests.

When members of Parliament sympathetic to the Puritan view became a majority, in 1629, King Charles I dissolved Parliament, and ruled by decree for eleven years.

Fortunately for the Puritans, there was an alternative to suffering persecution: emigration. As one theological opponent put it (in what was meant as sarcasm:)

It was no hard matter for these Ministers and Lecturers to persuade [their congregations] to remove their dwellings and transport their trades. ‘The Sun of Heaven,’ say they, ‘doth shine as comfortably in other places; the Sun of righteousness much brighter! Better to go and dwell in Goshen, find it where we can, than tarry in the midst of such an Egyptian darkness as is known falling on this land.’ Ref

17th-century ship, perhaps the Increase

About 80,000 Puritans left England during the “eleven years tyranny.” In roughly equal numbers they went to Ireland, the Netherlands, the English colonies in the West Indies, and New England. A large majority (60%) left from the six counties in the east of England, including Suffolk, that had once been colonized by Scandinavians under the Danelaw. Ref

The “Great Migration” began with a fleet of eleven ships led by John Winthrop in 1630 and lasted until the restoration of Parliament in 1640. After 1640, emigration flowed briefly back to England, as some Puritans returned to help fight in the Civil War. Within a few years the King was overthrown, Puritan Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector, and persecution ran the other way.

Arrival of the Winthrop Colony in Boston harbor, by William F. Halstall (1880.) The central ship is Winthrop’s flagship Arabella.

Puritans tended to be better educated and more prosperous than emigrants to other colonies. The disappearence of men key to the local social structure alarmed the authorities. A Suffolk official wrote in 1633 to Archbishop Laud, asking that several ships about to leave Ipswich with 600 emigrants be “stayed.” Alarmed at “the overthrow of trade” and “increase of the adversaries to the episcopal state” likely if these people were “suffered to go in such swarms,” he suggested that an order be sent:

...for Mr. Dalton, parson of Woolverstone by Ipswich, who is a great stickler for transporting these people, that he may be inhibited further meddling in the business... Ref

As a young parishioner, Nathaniel heard many sermons by Mr. Dalton. Dalton likely recommended that he could better serve God in another place. As the youngest of four sons, Nathaniel may also have concluded that his prospects looked better somewhere beyond Woolverstone. The pattern of older sons remaining near home, while younger sons seek their fortunes on whatever happens to be the frontier at the time, reoccurs several times in the history of this family.

John Winthrop, Governor of the newly chartered Massachusetts Bay Colony, first disembarked at Salem in June of 1630. Still a rudimentary place, Salem had been founded four years before by colonists left stranded after the failure of earlier, underfunded projects and fishermen who left the successful Plymouth Colony because they found the Pilgrims there too strictly religious.

Not satisfied, after a week Winthrop sailed down the coast to another barely-established village, Charlestown, near the mouth of the river Charles. More ships from his fleet caught up with him there. The sources of water in Charlestown were limited and brackish. After the long voyage, many colonists were weak with scurvy. By the end of the hot summer over 280 had died.

Illustration of Governor Winthrop arriving in Salem, Massachusetts in 1630 Ref

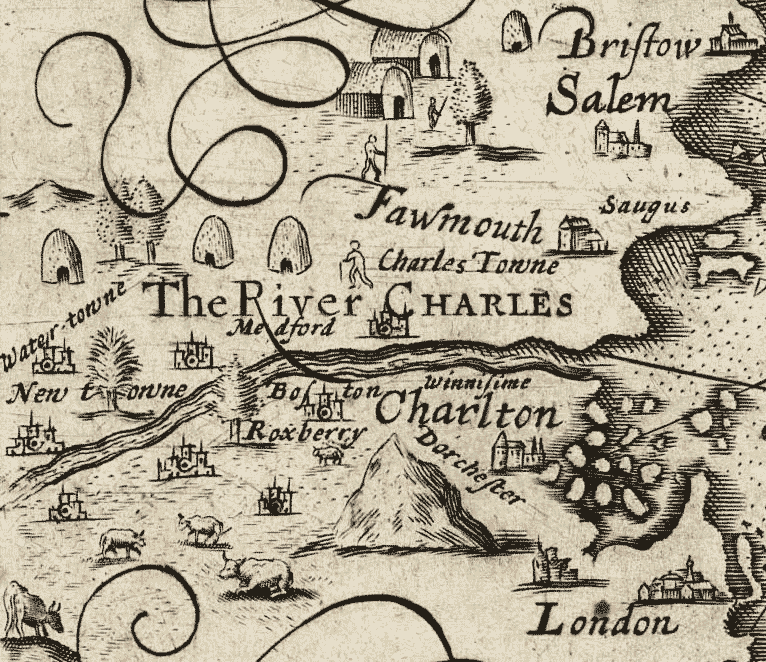

Detail of a 1635 map of New England by John Smith (better known for his earlier adventures in Virginia.) The relative location of towns is approximate. Charleston (Charlton) is given greater prominence than the city that quickly became dominant (Bofton.) The most prominent text (The River CHARLES) shouts the name of the King who funded Smith's expeditions.

There was a dependable spring across the river, Winthrop learned, on the Shawmut peninsula. In October the largest part of the fleet settled there, renaming the place Boston, after a city in Lincolnshire. Other parts of his fleet settled in towns established a few years earlier, including Salem and Dorchester, and founded new towns, including Cambridge and Watertown.

The Descendants of Isaac Colburn and other genealogies assert that Nathaniel Colburn was part of the group that went with Winthrop to Boston, and that “Later he moved up the Charles to Watertown.” None of these references cite any primary sources that place Nathaniel in Boston or Watertown prior to his appearance in Dedham in 1637.

Though Nathaniel's name does not appear on any of the transcribed passenger lists of ships that crossed the Atlantic during the Great Migration, this is not unusual. The names of many people who were undoubtedly present in early Massachusetts do not appear on any surviving passenger list, including Timothy Dalton and the woman Nathaniel later married (Priscilla Clarke.)

Church authorities suspended Timothy Dalton from his clerical duties in Woolverstone in April, 1636. He fled England, with his family, either late that year or early 1637, before he could be tried by the High Commission Court. His biographer suspects that, like many other Puritan ministers, he travelled in disguise. Ministers were forbidden to emigrate without the permission of church authorities.

If the histories that say that Nathaniel emigrated in 1630 are correct, he came by himself at age 19, spent several years in Boston, and later caught up with his former minister in Watertown.

More likely he came over with Dalton, in 1636 or 1637, perhaps in Dalton’s employ. Since Dalton likely travelled under an assumed name, perhaps Colburn, who would have been 25 or 26, did so as well.

The Founding of Dedham

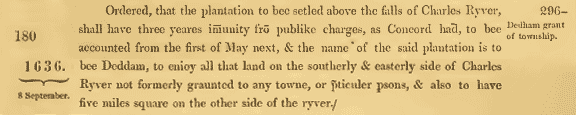

By 1635, Boston, Watertown and other early villages were already beginning to seem overcrowded to land-hungry farmers from East Anglia. The Massachusetts General Court called for the establishment of new towns further inland, both to relieve population pressure and to create a buffer between the coastal towns and potentially hostile Native-American tribes living to the west. Meeting in September in Newe Towne (later Cambridge,) the Court ordered “that there shalbe a plantation settled about two myles above the falls of Charles River” (referring to falls in present-day Newton.) Ref

The court commissioned three surveyors, who reported back in early 1636. They proposed a a “newe towne upon Charles Ryver” with dimensions similar to that of towns already established:

the bounds of the town shall run from the market tree by Charles Ryver on the north west side of Roxberry bounds, one mile & half north dart, & from thence three miles north west, & so from thence five miles south west, & on the south west side Charles Ryver from the south east side of Roxberry bounds, to run four mile on a south west line,with borders running three miles this way, four miles another, a mile or so a third. Ref

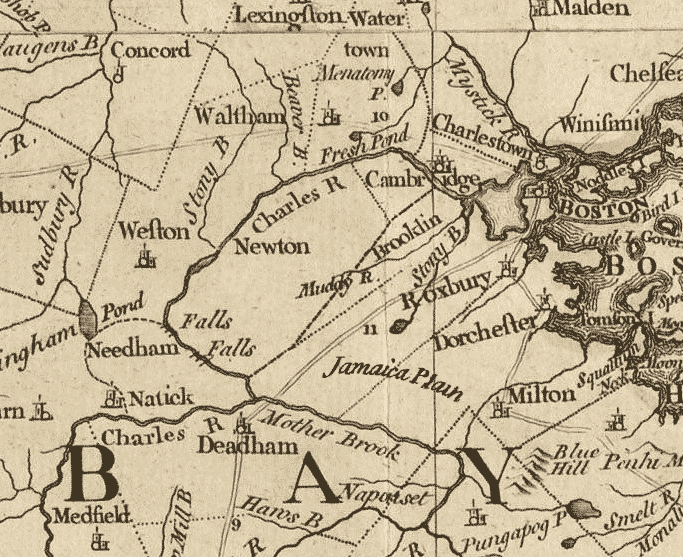

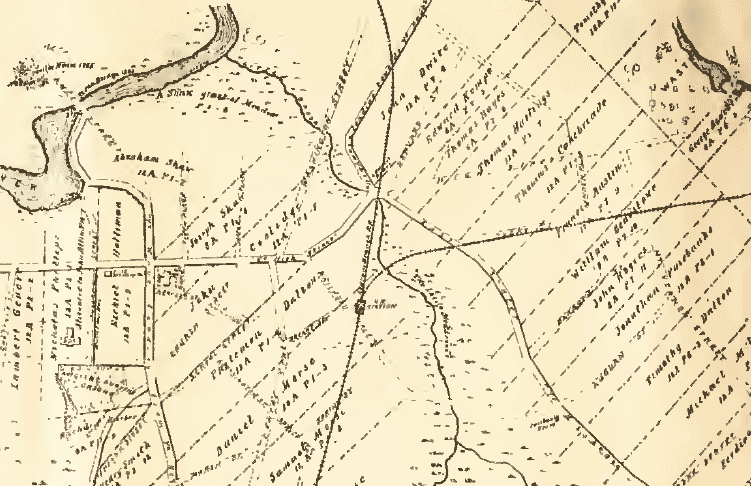

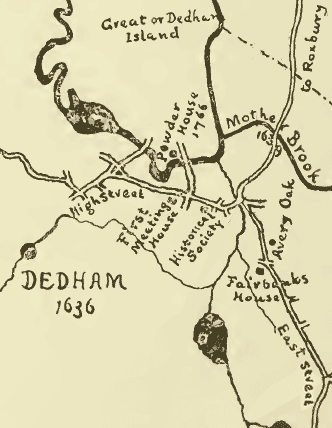

Detail of A map of the most inhabited part of New England (Jeffreys, 1774.) “Deadham” is southeast of Boston, at the point of a large bend in the Charles river. “Water town” is downriver, at the top of the map, extending north from the river at “Fresh Pond.”

Meanwhile a group living in Watertown heard the Court’s call for a new settlement, understood the opportunity, and began making their own “improvements” in an area above the falls. They chose a place the Algonquian natives called Tiot, “land surrounded by water.” Ref The place offered a ready supply of firewood on its “uplands,” abundant fish in its streams and “swampes,” and remarkably broad stretches of meadow perfect for raising crops or cattle. It was such a perfectly inviting spot for the farmers of East Anglia that they named it “Contentment.”

That this paradise seemed made for human habitation was not entirely an accident of nature. For centuries, Native Americans set fires each November, creating fields that would attract wild game and allow them to periodically plant corn, beans and squash.

In the century before the Puritans arrived, the natives of Massachusetts had been decimated by diseases introduced by European fishermen and explorers. Epidemics, primarily but not exclusively smallpox, wiped out a large part of the population. By the time the Puritans arrived, land that had once supported a large native population seemed miraculously empty of inhabitants, and “meadowes” sat there just waiting for their crops and cattle.

Native American women planting corn in a cleared forest

In September, nineteen men signed a “peticion” to the colony General Court. They asked the court to

“Ratifie vnto your humble petitioners your grante formerly made of a Plantacion aboue the Falls.”

Their petition boldly ignored the limited recommendations of the official surveyors, requesting instead

...that we may posesse all that Land which is left out of all former grants vpon that side of Charles Riuer. And vpon the other side five miles square.

Excerpt from the 8 September 1636 meeting of the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony establishing the new town of Dedham Ref

A month later, the Court largely agreed to the petitioners' request. The only major change made was to reject the name Contentment. The new town would be called Dedham, after Dedham, Essex, where some of the settlers had been born. “Contentment” later became the town motto.

The members of the Court likely had only a vague understanding of how far the Charles River actually stretches. The settlers may have had a clearer sense of how bold their proposition was, or perhaps they were just lucky. In any case, as it turned out these nineteen men had scored an unparalled deal.

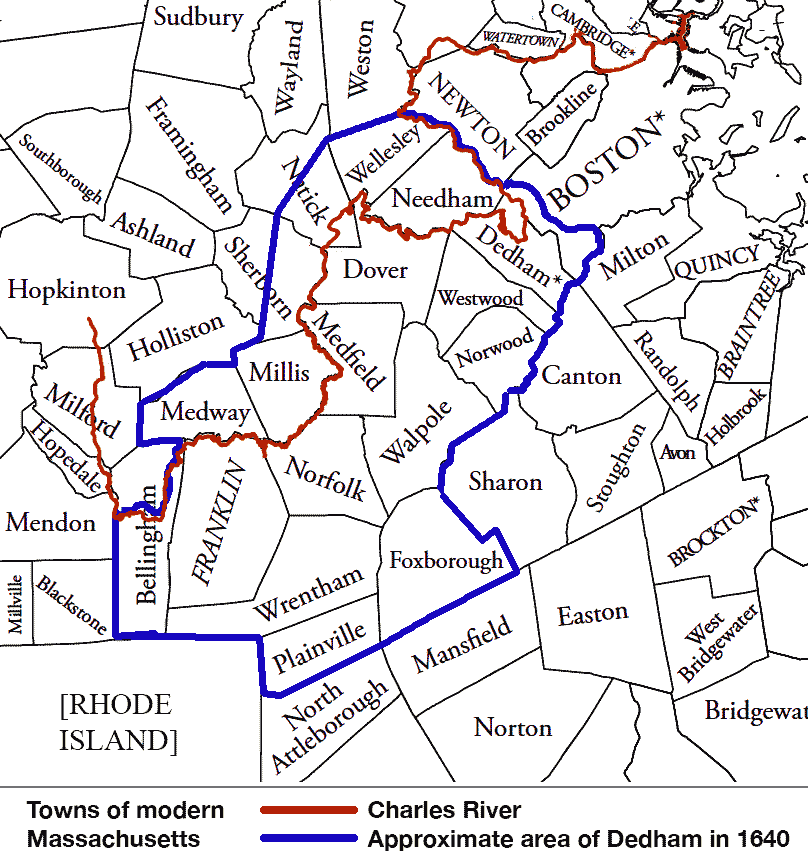

Instead of the roughly ten square miles recommended by the Court's surveyors, they now controlled over two hundred square miles, stretching from inside the borders of modern Boston all the way to the Rhode Island border.

The Court never granted anything close to this amount of territory to any other town. Concord, another frontier town founded about the same time, received six square miles. Boston, at the time, comprised less than two. Dedham today, after giving birth to fifteen "daughter towns," covers 10.6 square miles - approximately what the Bay Colony surveyors originally recommended.

The original Dedham grant included what are today sixteen towns in modern Norfolk County, parts of modern Boston, and parts of Natick and Sherborn in Middlesex County.

Of the original nineteen Proprietors, more than half never settled in Dedham. Two that did make the move promptly died. After a few years, several more chose to pursue other opportunities not quite so far out in the wilderness.

Dedham needed settlers. To induce families to move to this frontier outpost, the Proprietors offered free land - twelve acres to married men and eight to bachelors - and membership in the town. Those willing to share the hardships of the frontier became Proprietors themselves, and shared in both the rewards and responsibilities joint ownership entailed.

Not just anyone could join, however. Candidates had to be both capable of taming the wilderness and of high moral character, by Puritan lights:

We shall by all means labor to keep off from us all such as are contrary minded, and receive only such unto us as may be probably of one heart with us...

There was also a time restriction: those granted land had to actually make Dedham their principal residence within a year, or the land would be given to someone else. From the minutes of the November 1636 town meeting (still held in Watertown:)

Wheras our Towne of Dedham being far Remote from other Townes... we shold enioye what number of people we may for our better saffety from danger... Wherfore we doe nowe by a generall consent order that all those wch haue or shall heerafter Receive Lott in our sayd towne: shall before the First daye of November next become Inhabitant within our sayd Towne to imryve their sayd Lotts & soe shall ther constantly Remayne dwelling... And yf any pson or psons haveing Lott shall not pforme heerin according to the true meaneing hereof: That all such graunte or graunts made... shall become voyde as yf the same had never ben.

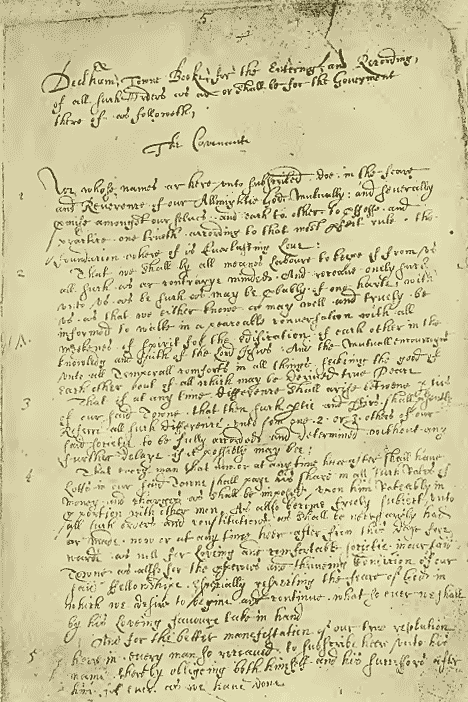

The Dedham Covenant

In 1636, how the Massachusetts Bay Colony would be governed was still a work in progress. The King, and most of those who exercised power in his name, were on the far side of a wide ocean. Frontier towns like Dedham, as a practical matter, had to create their own government. The Puritan way was to mutually agree on the principles by which they would live together, and write them into a “covenant.” Puritan town covenants were first steps toward what became the American form of democracy.

At each monthly meeting in 1637, the Proprietors most committed to the new town presented friends and relatives as candidates for admission. Those accepted signed the covenant, became a Proprietor, and were allotted their twelve homestead acres.

Among the first to homestead in “Contentment” and sign the Covenant (signer #4) was Philemon Dalton, younger brother of Nathaniel Colburn’s pastor Timothy. A prosperous 45-year-old linen weaver back in England, he had arrived in Massachusetts, with his wife and son, in April 1635. By the time he appeared among the first settlers of Dedham, he and three partners had already purchased 300 acres adjoining the Dedham grant. At the January 1636 town meeting the town agreed to purchase their land and annex it.

Ref

The Dedham Covenant, as written out by Edward Alleyne (Allen) Ref

In July 1637, after “some agitacion concerning Mr. Daltons Joyneing with us,” Philemon's brother Timothy was admitted as Proprietor. To his likely disappointment, he was admitted not as a minister but in a “Civill condicion” only. Choosing a minister was a very serious matter for Puritans (among other considerations, it usually meant lifetime employment.) Dedham did not call a minister until November of the following year.

Nathaniel Becomes a Proprietor

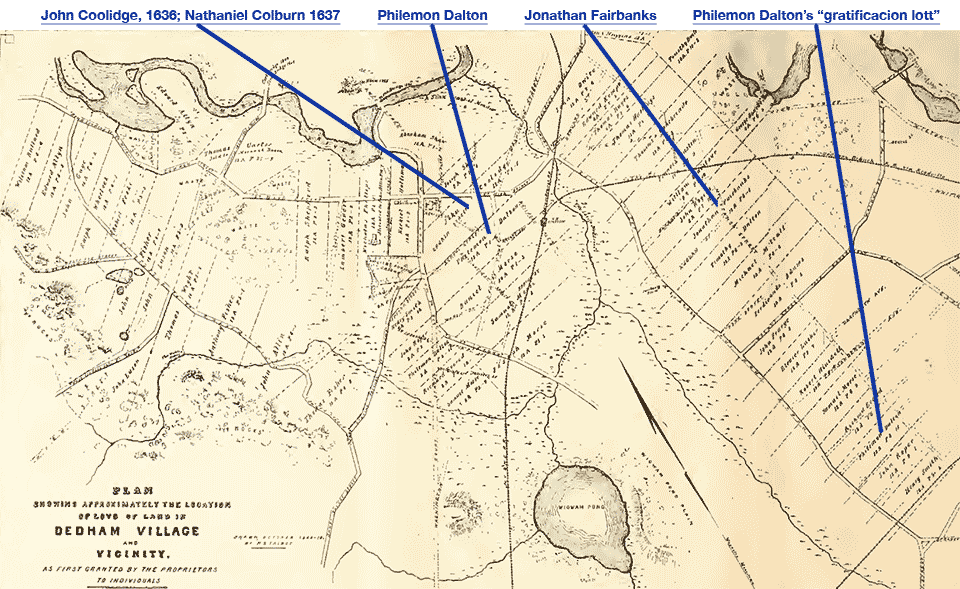

Philemon Dalton’s homestead property was near the center of High Street, one of the principal streets in Dedham then and now. He had also been given a second, “gratification lott” in compensation for land he had previous purchased, annexed by the town. He could hold this lot until turning it over to a friend or relative.

According to the minutes of the next town meeting, August 11 1637:

It is consented that Nathaniell Colborne may haue Philemon Daltons grateficacon Lott, brenging crtifficate & subscribeing accordingly.

Plan Showing Approximately the Location of Lots of Land in Dedham Village and Vicinity as First Granted by the Proprietors to Individuals (Dedham Historical Society, 1883)

At age 26, Nathaniel was younger than almost all the other attendees at his first meeting. Most of the others were between 37 and 61. Of the few in their 20’s, most had arrived with their fathers or older brothers. Whether he had come as Timothy's servant or as his most devout congregant, the Dalton brothers seem to have taken the young man under their protection, and Dedham needed settlers. For a youngest son of a Suffolk farmer venturing out into the world, this was a stroke of good luck.

Almost immediately, his luck got even better. Philemon Dalton's “gratification lot” was small, and on the edge of town. By the time Nathaniel signed the Covenant, another plot had opened, in the very center of the new town. This plot had been granted to John Coolidge, one of the nineteen original Proprietors. Coolidge attended all the 1636 meetings held in Watertown, but in 1637, when the monthly meetings started being held in Dedham itself, he failed to show up. The first order of business at the August 1637 meeting gave him a warning:

Wheras Certeyne Lotts haue long lyne wast vpon the names of John Ellis & John Coolidge wth out any imployment. It is ordered yf they doe not wthin 6 dayes set on to build & impve the sayd lotts as is Requesite. That then the sayd Lotts shal be at liberty to be disposed of vnto some other men.

Coolidge elected to stay in Watertown (where he prospered, and became the great-times-nine-grandfather of President Calvin Coolidge.) When Coolidge’s choice plot reverted to the town proprietors, they gave it to young “Nathaniell Coaleburne.” He signed the Dedham Covenant in October 1636, 45th of an eventual 125.

Close-up of the map of allotments to the orginal Proprietors, with Coolidge and Dalton plots at center. Near the left edge is the location of the original Meeting House.

The lot was described as follows:

Twelue acres more or lesse as it lyeth betweene Joseph Shawe towards the North & Philemon Dalton for the most part on the high Streete towards the South : And abutts vpon the litle Medowes towards ye East : & vpon the waye leading from the Keye [the bridge over the Charles] to the Pond towards the West with: the high Streete leading from the Litle Bridge Runing through the same corner wise.

The timing of his arrival was fortunate. At the August 1637 meeting it was also decided to roll up the welcome mat “for the mean tyme:”

For as much as our portion of allottment that we haue formerly Resolved vpon are nowe fully compleate according to our Intendements We doe nowe therfore fully agree by a generall consent that noe more Lotts shalbe graunted out vntill a further viewe be made what accomodacon may be fownd, for compfortable enterteynem of others. In the meane tyme those whoe haue given their names desiering to haue Lotts wth vs shall haue a negatiue Answer.

Though his brother Philemon had arranged a nice farm for him in Dedham, Timothy Dalton had not gone to Cambridge (as a scholarship student) to become a farmer. He soon moved north to take up churchly functions in Hampton, New Hampshire (at the time still within the Massachusetts Bay Colony.) By 1642 Philemon had moved on as well. According to the Dalton biography, “He had brains as well as money, and was full of energy and business sagacity... Dedham speedily became too small a field for him...” He joined his brother in Hampton for a time, but soon, “tired of Hampton and its dullness... removed to the more active and prosperous Ipswich.” Ref

By the time the Dalton brothers moved on, Nathaniel Colburn was a well-established Proprietor with no need for further mentoring. The original Colburn farm is now the heart of Dedham. Just east of the courthouse, it includes Dedham Square and the building of the Dedham Historical Society (as well as the “Museum of Bad Art.”) How it became the center of “urban Dedham” will be explained later.

Detail of a Dedham Historical Society map showing the layout of streets and major landmarks in 1636. One modern landmark (the Historical Society) sits on the original Colburn plot.

Homeowner

A good idea of what it was like can still be seen in Dedham today, in the Fairbanks House. Built between 1637 and 1641, it is the oldest surviving timber-frame building in the United States. Still owned by descendants of the Jonathan Fairbanks who built it, it is now a museum.

The Fairbanks House, Dedham, in 1936. Built 1637-1641, it is the oldest surviving timber-frame house in America. All photos by Thomas T. Waterman, June 1936 (Library of Congress.)

We tend to imagine the early English settlers building their own houses, as pioneers often did in the later era of 19th-century western expansion. However, professional builders were among the first English immigrants to America... The Fairbanks House is constructed in the style common in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in... the East Anglian counties of Essex and Suffolk. Like the Fairbanks House, the typical houses there were of timber frame construction with wattle-and-daub insulation.

View of beams and joists above weaving and spinning implements, second-floor workroom of the Fairbanks House.

View of door and fireplace, “hall chamber” second floor.

The Fairbanks House website describes the original house as follows:

"The original house had four rooms surrounding the massive center chimney – two on the first floor and two on the second with an attic above that. Insulation was provided by wattle and daub, a mixture of clay, straw and lime, which provided a smooth interior finish to the walls as well.

View of the first floor "parlor."

"As you stand inside the front door of the house, the room on your right side was originally called the parlor, and the room on the left was the hall (we would call it the kitchen). On the second floor were the parlor chamber and the hall chamber. “Chamber” was the word used for “upstairs room,” so the parlor chamber was the room above the parlor, and the hall chamber the room above the hall... By modern standards these were close quarters for a family of eight, but at the time the house was rather grand. Dedham’s first recorded property assessments were made in 1648, and Jonathan’s house was valued in the top 25% of Dedham property."

In the 1648 assessment, though Nathaniel Colburn’s house was valued lower than that of his neighbor “Fayerbank,” it was also in the top 25%. Whether or not Nathaniel Colburn’s house was as grand as the Fairbanks House to begin with, as time went on and his position as Proprietor made him wealthy, he undoubtedly improved it. His family of 11 children was even larger than that of his neighbor Jonathan.

The “hall” (kitchen) looking east.

The Fairbanks House “hall," looking west.

By the 1660 assessment Nathaniel's house was valued at 12 pounds, edging out Jonathan’s, valued at 10 pounds 8 shillings.

In his will he left the house to his son Benjamin, but provided that his widow would live in “her Dwelling in ye Parlour end of my house.” This suggests that, at least by the time he died, Nathaniel’s house was something like what can still be seen today in the original section of the Fairbanks House.

Husband

Now that Nathaniel had a farm, and a house, it was time to get married (according to the Covenant, he could only keep his full twelve acres if he was married.) He promptly did so 25 June 1639, marrying Priscilla Clarke.

Priscilla was born in 1613 in Banham, Norfolk, England, the 8th of 11 children of Thomas and Mary Clarke. She came to Dedham from Watertown with four siblings. Exactly when they emigrated is unclear, although the passenger list of the ship Abraham in 1635 includes a “Clark Jo” aged 20, the age of her brother John at the time. Her brother Rowland owned land in Dedham by 1637 but died the following year (some genealogies confuse their grandfather, also Rowland, with this brother; others confuse this Rowland Clark with another Rowland from Bedfordshire and say that he was her father.)

In emigrating together, the Clarke siblings were more typical Puritans than Nathaniel, who came without other family members. According to David Hackett Fischer, “By comparison with other colonies, households throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut included large number of children, small numbers of servants and high proportions of intact marital unions.” Ref Marital bliss was enforced by law: Puritans thought life in a “covenanted family” was the only proper way, and made it illegal to live alone. Officials would force a stubborn bachelor to either “settle himself with a family” or “settle himself” in the House of Correction. Ref

| Priscilla Clarke | (1613-1692) | ||

| Thomas Clarke | (1567-1638) | and Mary Hobart (1574-1642) | Died Banham, Norfolk |

| Rowland Clarke | (1529-1579) | and Margaret Micklewood (1533-1593) | Banham |

| Robert Clarke | (1489-1558) | and Alice (1492-1553) | Banham |

| John Clarke | (1460-1548) | and Rebecca Godfrey (1470-?) | Banham and Aldington, Kent |

| Robert Clarke | (1430-?) | and Katherina Edingham (1435-1460) | Woodchurch, Kent |

| Henry Clarke | (1400-?) | and Matilda (1407-1430) | Woodchuch and Echingham |

| Thomas Clarke III | (1375-1446) | and Sarah Forde (1375-?) | Wrotham, Kent |

| Thomas de Clark II | (1350-1446) | and Eleanor Bowlinge (1352-?) | Wrotham, Kent |

| Thomas de Clerke | (1315-1369) | and Elizabeth Conley (1317-?) | Woodchurch, Kent |

Up to this point the online genealogies seem trustworthy. Some however take the lineage back to a Norman knight who accompanied William the Conqueror and fathered many generations of aristocrats.

Entries for the first Thomas (born 1315) in the table above sometimes read: “Thomas de Clark, II (de Clare).” A name from the highest levels of post-conquest English aristocracy, the de Clare family began with an illegitimate half-brother of William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy who became King of England after 1066. For centuries the de Clare family ruled huge parts of England, including Clare, centered on a castle in western Suffolk, and Gloucester, on the opposite side of the country next to Wales.

Coat of arms of the de Clare family

The Battle of Bannockburn, from a 1440's manuscript of Scotichronicon by Walter Bower

Some ten generations later, the name “daughtered out,” when the only son of Gilbert, 6th Earl of Hertford and 7th Earl of Gloucester, died in 1614 at age 23 fighting the Scots in the battle of Bannockburn. Or did it?

The young man's widow, Maud, claimed to be pregnant. For over a year the huge de Clare estate was kept intact in the hope that there would be a male heir. This was a particularly big deal because the unfortunate young man’s mother, Joan d’Acre Plantagenet, was a daughter of King Edward I “Longshanks.”

King Edward II eventually decided that there was no male heir to the de Clare estate, and divided it between the husbands of the last Earl’s sisters.

At some point, perhaps when genealogy became a popular sport in the 19th century, someone seems to have noticed that if you add the honorific “de” of French aristocratic names to the ancient, honorable but commoner family name Clarke, and drop the letter 'k,' you have “de Clare.”

The first Thomas “de Clerke” happened to have been born in 1615, the year after Bannockburn.

Could Maud actually have been telling the truth, and had a son? And for some reason of palace intrigue, her son grew up in Kent, disinherited, under the name de Clarke? Some genealogies assert these suppositions as fact, listing Matilda “Maud” De Burgh as Thomas de Clarke’s mother and Gilbert de Clare, 8th Earl of Gloucester as his father.

This sort of wishful thinking has a long history. Thomas Hardy made such dreams about distinguished ancestors central to his Tess of the D’Ubervilles.

Caerphilly Castle, in the Welsh Marches, seat of the last two de Clare Earls of Gloucester

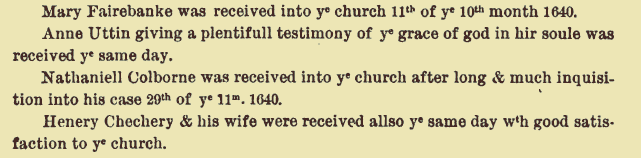

Priscialla and Nathaniel Join the Church

Joining a Puritan church was not an easy matter. Neither was creating a church in the first place. From the Wikipedia history of Dedham:

While it was of the utmost importance, “founding a church was more difficult than founding a town...” Only ‘visible saints’ were pure enough to become members. A public confession of faith was required, as was a life of holiness. All others would be required to attend the sermons at the meeting house, but could not join the church, nor receive communion, be baptized or become an officer of the church.

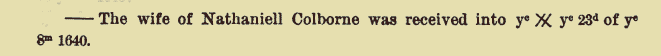

It took Nathaniel three years to be admitted to the church, and then it was only “after long & much inquisition into his case.”

What it was about his “case” that required “much inquisition” is lost to history. The entry for most accepted members reported no such inquisition.

His wife Priscilla had already been accepted three months before, without mention of any issues with her “case.”

The policy written into the town covenant to “receive only such unto us as may be probably of one heart with us” seems to have worked. Despite the tough rules, by 1648 70% of the men and most of the wives (in some cases the wives only) had become members of the Church. Dedham escaped the religious battles that roiled other New England towns. According to the Dedham Historical Society’s Capsule History of Dedham, “church records show no instances of dissension, Quaker or Baptist expulsions, or witchcraft persecutions.”

Woodreeve, Fence Viewer, Surveyor, Sealer, Selectman

In 1642 the town assigned younger Proprietors the jobs of inspecting fences and overseeing the use of common forest land for wood.

From 1642-1647 he served as Fence Viewer (in charge of inspecting fences) and Woodreeve. A reeve is an overseer; a woodreeve is someone who oversees the forests and/or the wood supply. In the spring a woodreeve would oversee the burning of ploughed fields and clearing of land to be used for grazing. Once all the wood was exhausted from their twelve-acre homestead lots, settlers needed to apply to the woodreeves for permission to “cut wood and timber, to cut hoop poles, and peal bark on the common lands. "The frequent practice of cutting without leave caused much difficulty.” Ref

In 1647 the town promoted Nathaniel to surveyor. At first he was deputed to make adjustments to lots within the established parts of town. Later the town asked him to lay out roads linking Dedham to other places, then to lay out entire new towns as they were carved out of the vast Dedham grant.

Nathaniel and another young Proprietor, charged with finding the best way for a road around a swamp to the sawmill, have made their report.

For twenty years Colburn was Sealer of Weights and Measures.

In 1662 be became "Clarke of the market," later called “Sealer of Weights and Measures.” Officials of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts still bear this title today.

He was first chosen to be one of the seven Selectmen in 1650, when he was 39. He served again 1658-1660 and 1666-1667. Selectmen “were men of proven ability who were known to hold the same values and to be seeking the same goals as their neighbors” chosen “by general consent” and given “full power to contrive, execute and perform all the business and affairs of this whole town.”

Dedham records for Nathaniel's election to Selectman in 1666.

Dedham originated the Selectmen system in 1639, when the number of Proprietors at the monthly meetings became too numerous for direct democracy to function smoothly. The system soon spread to most towns in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. New England towns are still governed by Boards of Selectmen today.

Consistency in spelling was not highly valued in the seventeenth century (members of the court of Charles II found it amusing to sign their names in as many different ways as they could imagine.)

On a petition to the Court concerning a land dispute with Indians living in Natick, he is Nathanell Coalburn.

On a single page of the Dedham (or Deadham) records in 1666, Nathaniel’s family name is spelled Coalburn, Coleburne, Coaleburne and Colburn.

On another petition three years later, he signs himself Nathanaiel Colburne. His son John is now a Proprietor as well.

His signature in 1676 on the inventory of the estate of a leading citizen of Dedham seems to have it Colborn or Colbarn. Only in the next generation did the name settle on Colburn.

In 1676 he is Nathanel Colbarn.

"Land Dividends"

Becoming covenant-signer #45 of Dedham in the seventeenth century could be compared to becoming employee #45 at a very successful start-up company in the twenty-first. It took a lot longer then for the payoff than it does for the early employees of the Facebooks and Twitters of today, but when Nathaniel died he was able to bequeath farms to each of five sons and two daughters - quite an accomplishment for a young man who arrived in Massachusetts with no family connections, little education and few resources besides his own energy.

In the early years, most Dedham land was held and used communally. Each family had its 12-acre farm, clustered together for protection. These were carefully plotted so that each included a strip of meadow that could be planted right away before cutting into the forest. Cattle were raised in a communal 532-acre tract called the “herd walk” west of town. So that everyone had access to fishing, land bordering bodies of water was also owned in common.

From time to time the Proprietors would award themselves “deuidents” in the form of land, dividing up tracts of wooded uplands, meadow, and “swampe.” (This spelling of “dividend” seems unique to early Dedham.) Sometimes these parcels were small, and sometimes huge.

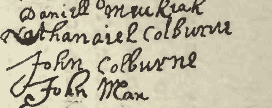

Excerpts from the record of a December 1644 meeting, during which the seven Selectmen awarded parcels of land totalling over 350 acres to the 83 current Proprietors. Nathaniel drew a low number this time, and so was the 73rd man to choose from the land being distributed. Since the amount of land was "proportioned according... to mens estates," and he is a senior Proprietor already owning considerable land, he is granted a larger parcel ("5 acres 3 roods") than that given to most.

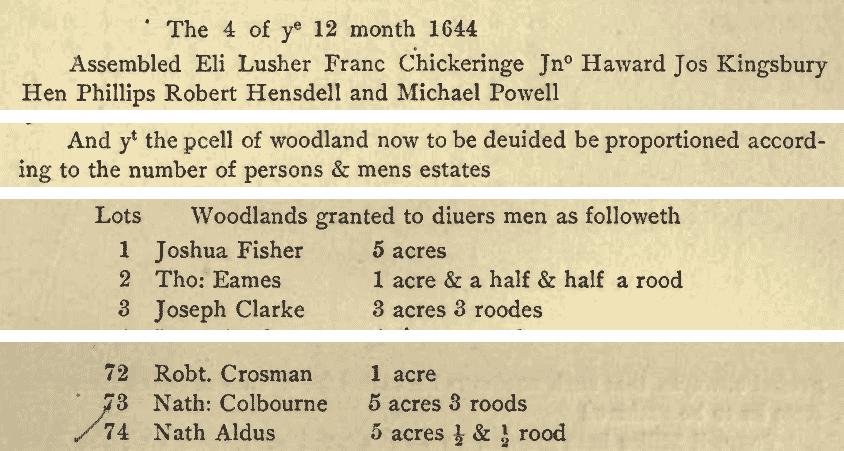

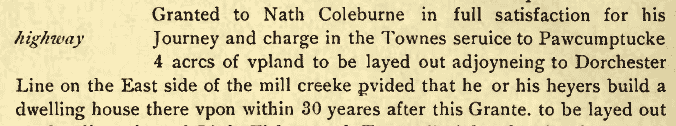

19th Century depiction of Rev. John Eliot preaching to “praying Indians.” Adopting a Native custom, Eliot preached from prominent boulders, which became known as "Eliot's pulpits."

A more complicated deal involved the creation of Natick in 1651 by missionary priest John Eliot as a town for “praying Indians.” The 2000 acres the General Court allotted to this experiment conflicted with the huge Dedham grant. Colburn, as Selectman at the time, was one of the complainants in a lawsuit brought before the colony General Court. Eliot and his "praying Indians" prevailed, and won the right the right to stay where they had settled.

As consolation, the Dedham Proprietors gained the right to choose a tract four times the size given to the Indians in Natick, anywhere to the west that had not yet been claimed. Theoretically, they could have chosen any tract between Dedham and Lake Ontario, since Massachussetts supposedly owned everything between two lines of latitude, extending through what is now northern New York State and beyond.

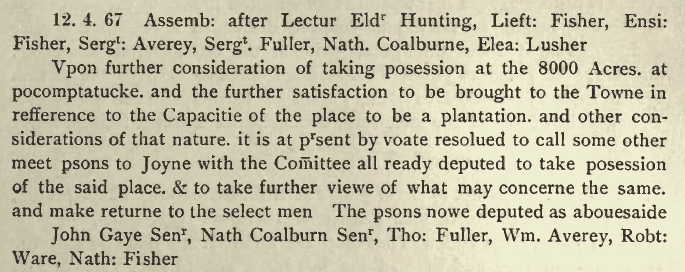

Agents from Dedham chose 8000 acres in the Connecticut River Valley that belonged to the Pocumtuck ("pocomptatucke" and "Pawcumptucke" in the town records), an Algonquin tribe that had been largely destroyed by smallpox and wars with the Mohawk. A few remnant Pocumtuck were found to sign deeds ceding "Indian title" to the land. Ref

In 1667 the Dedham Proprietors exercised their rights to the Connecticut Valley land awarded in a settlement a decade before. A Selectman at the time, Colburn was one of those chosen to take posession and determine how the land would be used.

The new town became Deerfield. As usual, Dedham Proprietors were awarded lots. Those who did not have sons willing to relocate to Deerfield (including Nathaniel) sold their land to someone who did want to move out to the new frontier.

Dedham often used parcels of its plentiful land to pay for services rendered. In 1669 Nathaniel was awarded land in compensation for his work surveying and laying out Deerfield ("Pawcumptucke.")

John Eliot's translation of the Bible into the Massachusett language was the first Bible printed in America. (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

John Eliot’s “praying Indians” thrived at Natick until, during King Philip’s War, fear of Native-Americans of any kind put the colony in a panic. In one of the most shameful episodes in Massachusetts history, the peaceful Christianized natives of Natick were imprisoned, in appalling conditions, on an island in Boston Harbor. After the war the decimated survivors found their town burned to the ground. Soon Natick became just another town for English settlers.

In 1656 came major decisions: the communal fields near town were divided up, and there would be no more free grants of land to strangers. The rules for dividing up land were revised. “No one pretended that all should have an equal share.” A complicated formula was devised that included the valuations of each Proprietor’s current estate, the rights they held in the herd walks (the “cow commons,”) and in other commons that had been created for other animals. “Five goat commons or five sheep commons were computed equal to one cow common, and were used as fractions of a whole right.” Some adjustments were made when the formula “bore heavily on several poor persons.” After a tussle about whether certain Proprietors who had moved to Boston should have cow-commons rights despite having no actual cows on the commons, the 80 proprietors agreed on the division of 522 shares.

Thus after this decision, there were two distinct bodies. The proprietors and inhabitants, including non-proprietors. But for many years this distinction existed only in theory, for there were not any persons for many years in the town, who were inhabitants and at the same time non-proprietors. Ref

Colburn had become wealthy by this point. His share of both the “rates” (taxes) and land dividends was one of the highest of the Proprietors.

King Philip's War

In 1661, at a general meeting, the town decided to set up a new “plantation” at the furthest reaches of their grant, next to the Rhode Island border. The Indians living in the area called it Wollomonuppoag. In 1662 Nathaniel and two others were sent to “extinguish the Indian title,” and paid 24 £. 10s to Metacomet, Sachem (war chief) of the Wamopanoag, who the colonists called King Philip.

The Proprietors first voted to sell 600 acres at Wollomonuppoag for 160 £ to “persons fit to carry on the work in church and state.” When it proved difficult to find enough settlers willing to move so far out into the wilderness, they voted to instead divide up the tract according to the usual formula. Colburn was on the committee charged with laying out the new town. After reserving land for public buildings, burying grounds and highways, and giving certain lots to those who had already made “improvements,” the rest of the lots were distributed among the Proprietors by lottery.

Metacomet (ca. 1639 – August 12, 1676), also King Philip or Metacom, Sachem of the Wampanoag Ref

A small settlement finally began in 1669. The same year, King Philip sent a letter offering to sell the land at Wollomonuppoag. Though the Proprietors thought they had already purchased it, the Colony had a longstanding policy to agree to whatever requests the Indians made regarding title to land. Nathaniel was part of a small group sent to negotiate on Dedham’s behalf. Another deed was drawn up, and Philip was paid “a Holland shirt” and £17.0s. 8d. Once it looked like the new plantation would actually begin, “some of the Proprietors sold their interests in the lands to such persons as wished to go there and remain as inhabitants.” Colburn was likely one of the sellers, since none of his children are recorded as moving to the town, renamed Wrentham.

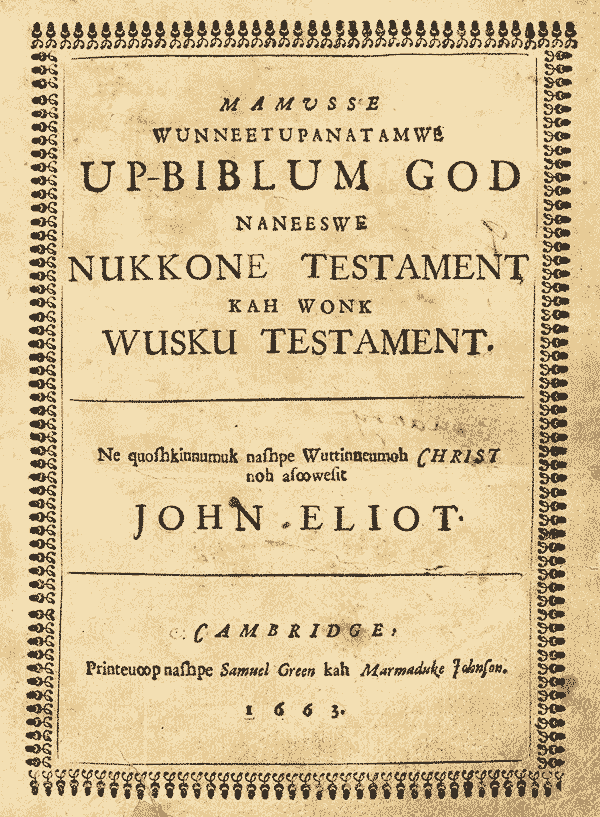

A few years later, tensions between the colonists and Native Americans led to the disastrous King Philip’s War. Almost four decades after Dedham was founded, in part to protect Boston from potential attack, the attack had finally come. By this time Dedham was itself protected by its outlying daughter towns. In 1675 the pioneer colonists of outlying Wrentham had to evacuate their homes, which the Nipmuc, Narragansett and Wamopanoags promptly burned to the ground. Medfield and Deerfield also suffered devastating attacks.

Indians Attacking a Garrison House by pushing a cart of burning hay toward the wooden military structure. This probably represents an attack on the Haynes Garrison at Sudbury, Massachusetts on April 21, 1676. Sudbury was just north of Dedham's western borders at the time. Ref

In this undated woodcut entitled Early American Conflict, colonists seem to be using superior firepower to repulse a group of Indians. (Wikipedia Commons)

In terms of percentage of the population, this was the bloodiest war in North American history: over 5,000 Native-Americans died, and over 2,500 colonists, about 5% of the population. It set back the expansion of the colonies by an estimated fifty years, and had even more disastrous consequences for the natives. Many were sent as slaves to plantations in the Caribbean. The Wampanoags and Narragansetts ceased to exist as organized tribes. Ref

Ten years after Philip's defeat, the citizens of Wrentham became concerned about the legitimacy of their claim to own the land on which their town had been rebuilt. At a meeting held to review the evidence in March of 1687, Nathaniel gave a deposition:

Nathaniel Colburn aged 70 year and upward testifie that I being at Wollomonuppoag when King Philip did make sale of thos lands which ware in the bounds of Dedham to thos men which Dedham Selectmen had sent up to trade with King Philip respecting ye same and I did see King Philip seal the deed in ye presents of divars Endens [Indians]who he said ware of his council. Ref

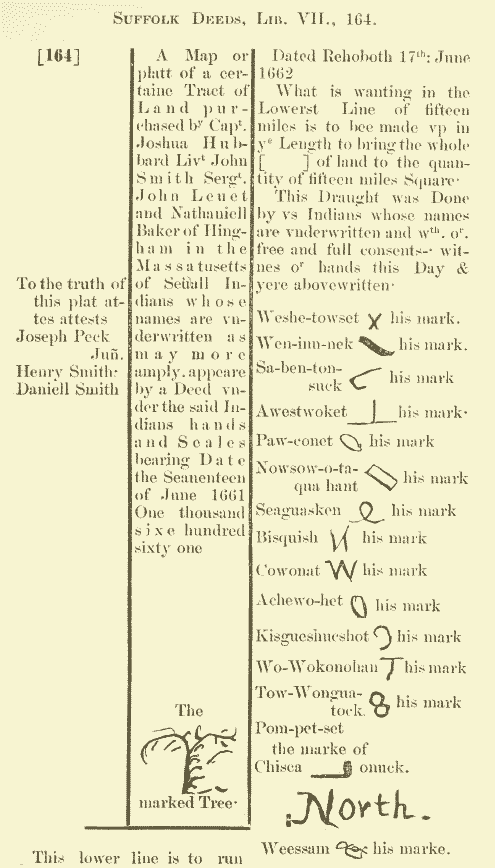

Transcript example of a deed by which a group of Narragansetts sold land to colonists. The colonists making this deal in 1662 were careful to record the names and "marks" of the Indians with whom they were dealing. Ref

Increase and Multiply

Puritans had a strong family ethic (and, despite their later reputation, an earthy, sensual attitude toward sex.) They tended to have many children, and the New England climate proved exceptionally conducive to their survival. The Puritans arrived in New England during the “little ice age,” when temperatures were much colder than they are today. According to David Hackett Fischer, this created “an exceptionally healthy environment for settlers from northern Europe.... Summer diseases such as enteritis, which were the great killers of children in the seventeenth century, tended to be comparatively mild in the Puritan colonies.“ The cold climate minimized the effect of insect-borne and water-borne diseases as well. On the other hand, Africans brought to New England tended to die of pulmonary disease. One of many reasons slavery never took hold in New England was that the purchase of such expensive assets, very likely to die of pneumonia, was too much of a risk. In Virginia, by contrast, Africans lived longer than Europeans since they were better adapted to tropical diseases. Ref

Priscilla and Nathaniel had 11 children, all of whom survived to adulthood, had children of their own, and lived out their lives in Dedham or daughter towns Medfield and West Dedham:

| Born | Married | Died | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sarah | 15 Apr 1640 | William Partridge | 1716 Medfield |

| Rebecca | 17 Feb 1643 | Elliot Hersey | 1670 Medfield |

| Nathaniel | 3 Mar 1645 | Mary Brooks | 1689 Dedham | Priscilla | 1 Apr 1646 | Joseph Morse | 1731 West Dedham |

| John | 29 Jul 1648 | Experience Leland | 1706 Dedham |

| Mary | 21 Jan 1650 | John Richards | 1685 Dedham |

| Hannah | 20 Jan 1653 | Thomas Aldridge | 1728 Dedham |

| Samuel | 25 Jan 1654 | Mary Partridge | 1694 Dedham |

| Deborah | 28 Jan 1656 | Joseph Wight | 1684 Dedham |

| Benjamin | 24 Sep 1659 | 1. Abiah Fisher 2. Bethiah Bullen |

1714 Dedham |

| JOSEPH | 1 Dec 1662 | Mary Holbrook | 1718 West Dedham |

In choosing plain Biblical names for their children, the Colburns followed the tradition of Puritans from East Anglia. The parents of most of those they married followed the same tradition. The one exception is John Colburn’s wife, Experience. Her family came from a different part of England (Yorkshire) where hortatory names were commonly used. Ref Her father’s name was Hopestill Leland.

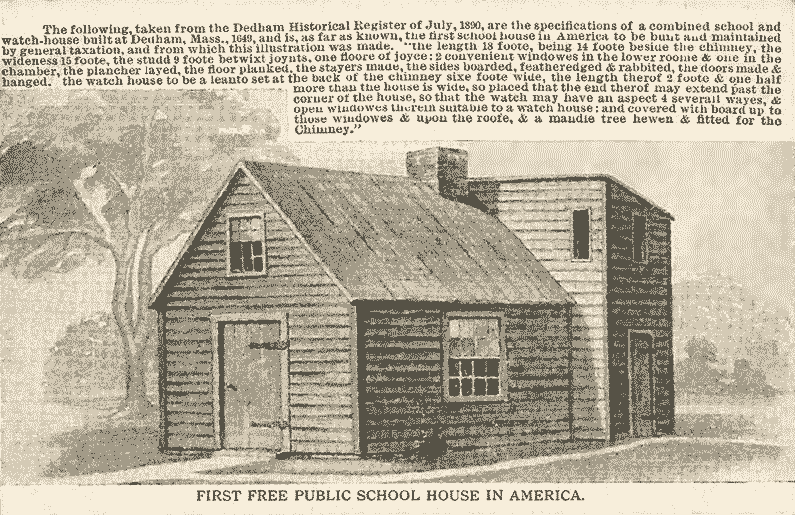

Illustration of the first Dedham school, based on details from early town records. From a 19th-century postcard.

The Colburn children attended the first free, tax-supported public school in America, established in Dedham in 1640. Puritans valued schooling, and tended to be more highly educated than other colonists.

Nathaniel was still living on High Street when he died, on 14 May 1691 at the age of 79. In his will, written the year before, he left his wife “the use, income & benefit of the whole Estate,” (unless she remarried, in which case she would get only a third) and “her Dwelling in ye Parlour end of my house.” Priscilla was 77 when he died. Ref

To four of his sons and his two eldest daughters he gave the houses and land on which they were already living (and on which they had been paying the “rates” for many years.) He gave sums of money to his three youngest daughters, long since married. His two eldest sons each received tracts in “Roxbury Plain,” then part of Dedham and now part of Boston. Son John froze to death in 1708, lost in the snow in Roxbury while returning home from Boston. There is a Colburn Street in Jamaica Plain today; for which Colburn it was named is unclear.

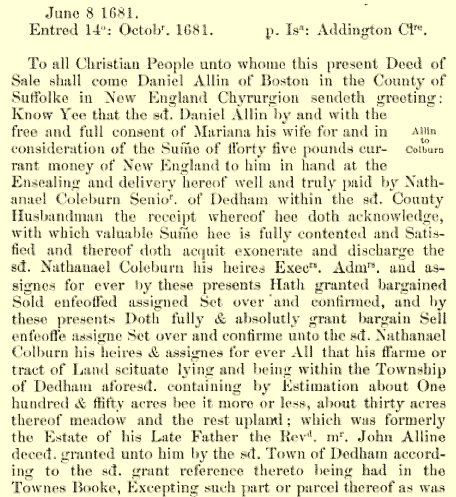

Two younger sons, Samuel and Joseph, were given “all the buildings they now possess & all my farme of One hundred & Fifty acres, that I purchased of Mister Allin... beyond the rockes” in West Dedham, which became a separate town (Westwood) in 1897. Nathaniel had purchased this undeveloped land in 1681 from the heirs of Dedham's first minister, John Allen (also Allin, Allyn, Allyne.) In honor and gratitude for his esteemed presence amongst them, when assigning "dividends" the Proprietors gave their Cambridge-educated pastor large, choice plots of land. Allen's heirs had moved to Boston and apparently were not interested in farming out in Dedham.

First part of a long 1681 deed in which Nathaniel Colburn buys land from the heirs of John Allen, the first Dedham minister. Ref

Before following the story of the branch of the Colburn family that moved to these West Dedham farms, we will tell a shorter story about what happened to Nathaniel’s original homestead. A century later, a cousin descendant’s bequest became a major turning point in the history of Dedham.

The "Colburn Grant"

To Benjamin, his fourth of five sons, Nathaniel gave “my owne present dwelling house & other buildings thereto... with all my homestead.” Why this particular son inherited the original farm while the others worked later acquisitions is unknown. Perhaps all the other sons chose to build their own farms on land that would become theirs on Nathaniel's death, and one son was needed to help the aging father. Perhaps Benjamin was his mother’s favorite. For a year, until she died on 12 Aug 1692, Benjamin shared the family homestead with Priscilla.

Benjamin became a leading citizen of Dedham, serving as Selectman several times. He and his heirs accumulated additional Dedham land. Though he had ten children, many died young. Two generations later, 24-year old Samuel Colburn became the sole heir to all the land accumulated by this branch of the Colburns.

Samuel lived with his mother in Nathaniel’s original homestead on High Street, near what is now Dedham Square. In 1756, during the French and Indian War, he volunteered to be a soldier, and promptly died from disease on an expedition to upstate New York.

Samuel’s will came as a shock to Dedham. He left his entire estate, after his mother died, to the Anglican (Episcopal) church.

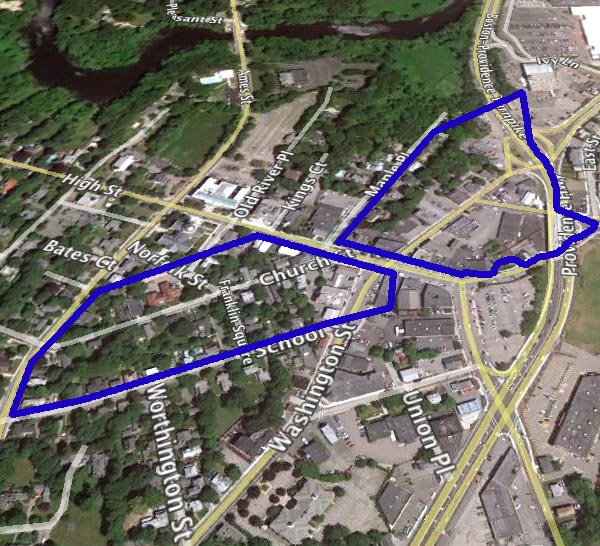

View of part of 21st century central Dedham, with Nathaniel Colburn’s first 12-acre farm (plus “meadowe” added later) outlined in blue.

The Anglican church! To a town still dominated by the descendants of Puritans, who had emigrated in part to get away from the Church of England and its “popish ways,” this was astonishing. Why he made this choice remains a mystery. He was not Anglican himself, though he had Anglican friends. It was perhaps a whim -- a young man’s secret gesture of disdain for conventional values before he rode off to war.

Like many Colburns over the generations, Samuel’s mother lived a very long life, dying at age 91, in 1792. Decisions made by the Episcopal Rector at that time, when the church finally inherited the estate, transformed Dedham:

Modern Church Street... first to be laid out, was the original urban street in the Town of Dedham, in the sense that it was intended to be bordered by house lots, as opposed to being merely a way from one farm to another. By Special Act of the Massachusetts legislature, the Episcopal Church was empowered to lease lots for periods of 999 years. Ref

Shopkeepers and artisans took over some of the lots, and created a “downtown.” Dedham was on its way from being a sleepy agricultural town to something else. By this point however the Colburn branch followed in this history was a generation away from Dedham, and headed off into "another wilderness."

Monument in Dedham Square.

Part of the farm of

Samuel Colburn, 1733-1756.

With forty-two others from Dedham he served in

the Crown Point Expedition of 1756.

Photo Bill Gasperini 2011